No products in the cart.

Return To ShopAnti Malaria Medications: The Past, Present and future of Anti-Malarial medicines

Anti Malaria: Past and Present

Anti Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease which occurs most commonly in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. These areas are hit the most because of the following factors; both species of mosquito which carry the disease exist there, the weather conditions allow transmission to occur all year round, and the low socio-economic stability of these countries can limit efforts to reduce transmission. Children and pregnant women are generally the most vulnerable groups to malaria, and this is because children have yet to develop any immunity to the disease and the immune systems of pregnant women are generally decreased.

In a report from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, it was estimated that globally 445,000 people died as a result of malaria, and the majority of these cases were young children located in sub-Subaran Africa.

Recently, Asian leaders have made a major push to focus on the fight against malaria. Countries including China, Malaysia and India within the organisation APLMA (Asia Pacific Leaders Malaria Alliance Secretariat, an affiliation of Asia and Pacific heads of government) are working together towards the mutual goal of eliminating malaria in the region by 2030.

There is also a malaria vaccine on the horizon, called PfSPZ, which claims to provide 100% protection against the disease. It has proven to be effective in laboratory studies where volunteers gained complete protection. It’s now currently awaiting its first large clinical trial, which will allow the effectiveness of the vaccine to be tested in a real-world application.

Researchers are working globally to tackle this life-threatening disease, and with good reason. As it stands, malaria is the leading cause of death in many developing countries. The impact of the disease also has huge financial ramifications, where the US alone has seen direct costs amounting to $12 billion per year. All efforts towards the treatment could hopefully eradicate the disease.

A recent study published in F1000Research investigates the chloroquine resistance among Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from Sudan. Chloroquine (chloroquine phosphate) is an antimalarial medication, which can be used both as a preventative and a treatment for malaria. Chloroquine was the first drug of choice for malaria treatment and this was a result of its high efficacy. It was used as the main treatment in Africa for over 50 years. It is also considered one of the safest and cheapest drugs, hence it’s popular use in LMICs.

Despite it being a well-established drug, its use has started to decline in Sudan. It’s speculated that this is a result of resistance to the drug in cases of malaria caused by P. falciparum. In this study, the researchers attempted to verify the genetic cause of resistance to chloroquine in P. falciparum isolates. This emerging drug resistance poses one of the greatest public health challenges to Africa.

The study took twenty confirmed P.falciparum cases from the East Nile hospital in Khartoum. The researchers then used nested PCR to isolate the mutation region in the PfCRT gene and amplicons were sequenced via the Sanger sequencing machine. The results of the study found that 80% of the field isolates possessed a codon mutation which allowed chloroquine resistance. This finding suggests a reason for the reduced use of chloroquine as a treatment for P. falciparum malaria.

Resistance to malaria medication is a growing concern and therefore efforts and projects like the APLMA and the malaria vaccine are of increasing importance, to limit the spread and devastation caused by this widespread disease.

What To Eat & Avoid During Anti Malaria?

When one thinks of Monsoons, the thought of Malaria is not far behind. It is a protozoal disease that weakens the immune system. This happens because of the heavy antibiotics used to treat the disease. Malaria is characterised by chills followed by fever, headache, diarrhoea, vomiting, etc.

It is associated with high-grade fever that is transmitted by female Anopheline mosquitoes. This mosquito transfers the parasite of the disease from one sick person to another. The parasite, when in the bloodstream, infects the red blood cells.

To treat malaria, there is no specific diet, but one needs to ensure adequate nutrition to help the body fight the disease. A diet for malaria should focus on boosting the immune system without causing harm to other organs like the kidney, liver or digestive system. It is best that a malaria patient has smaller meals throughout the day.

Eat Nutritious Foods

When the patient has a malarial fever, the body’s calorie and nutritional requirement increases. This is known as the BMR or Body Metabolic Rate. Also, the need to increase calorie intake depends on the rise in body temperature.

Consume a high carbohydrate diet. Choose rice over wheat and millets. Rice can be digested easily and can release energy faster. Fresh fruits and vegetables work wonders for malaria patients. According to studies, vitamin A and vitamin C rich fruits and vegetables like beetroot, carrot, papaya, sweet lime, grapes, berries, lemon, orange help to detoxify and boost the immunity of the patient suffering from malaria.

Go ‘Nuts’ over ‘Seeds’

When you have malaria you need to incorporate more phytonutrients into your diet that help to tackle antioxidative stress caused by an infection. Nuts and seeds are powerhouses of phytonutrients as well as healthy fats and proteins. When you feel like munching on something in between your meals and are wondering what to eat during malaria, nuts and seeds are always the best options as processed foods are completely out of your reach at this point in time.

Increase Fluid Intake

Unfortunately, at the time of fever, one experiences appetite loss, less tolerance and therefore, eating food becomes a challenge. To compensate for such a situation, one must drink glucose water, fresh fruit juices, coconut water, a sorbet made with lemon, salt, sugar and water and electoral water.

While drinking water, make sure it is boiled or sterilized. Take in fluids in every way possible- milkshakes, juices of fruits and vegetables, rice water, pulse water, stew, soup, etc. Doctors recommend a daily fluid intake of at least 3 to 3.5 litres, if not more. Fluids will help in washing out the toxins from the body via urine and stools and help you get well sooner.

Ajwain water is a wonder drink that you should add to your diet when you are suffering from malaria. Ajwain being a carminative (flatulence relieving property reflecting of drugs), reduces bloating and gas and works to keep your digestive system healthy.

Increase Protein Intake

There is an increase in the requirement of protein as one loose a lot of tissue. A diet of high carbohydrate and high protein is helpful as the body can utilise the protein for anabolic and tissue repair and building process. Eating curd, lassi and buttermilk is highly beneficial.

High temperature makes the body weak and reduces appetite. Food rich in protein helps to synthesize immune bodies, which can help to fight parasites. Try to incorporate fish stew, chicken soup, eggs and pulses in your diet.

Eat Fat in Moderation

Fats are necessary for the body, but moderation is the key. Using dairy fats like cream, butter and fats from milk products aid indigestion. These foods contain MCT or medium change triglycerides. Using excessive fats or eating fried foods can increase the risk of nausea, indigestion and loose bowels.

Keep fats as far as possible from your malaria diet. Load up on Omega 3 fats such as fish, fish oil supplements, flax seeds, chia seeds and walnuts. They work well in reducing inflammation in the body. Also, read top anti-inflammatory foods to include in your diet.

Foods to avoid

Avoid very high fibre foods like green leafy vegetables, fruits with thick skin, whole grain cereals. Stay religiously away from food high in fat content like fries, chips, pastries, anything with a lot of cheese in it, food made from maida, etc. Refrain from having food that is spicy and/or hot. It will result in unnecessary stomach problems and heartburn. Sauces and pickles shouldn’t be included anywhere in the diet for a malaria patient. Avoid intake of coffee, tea, cocoa, cola or any other caffeinated beverages.

It is important to work on vitamin loss by drinking electrolytes. Eating soups, stews or drinking fruit juices or dal water, coconut water, etc. are important. Vitamin C and A rich foods such as papaya, beetroots and other citrus foods, etc. with vitamin B complex are important for a malaria patient.

Disclaimer: The information included at this site is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for medical treatment by a healthcare professional. Because of unique individual needs, the reader should consult their physician to determine the appropriateness of the information for the reader’s situation.

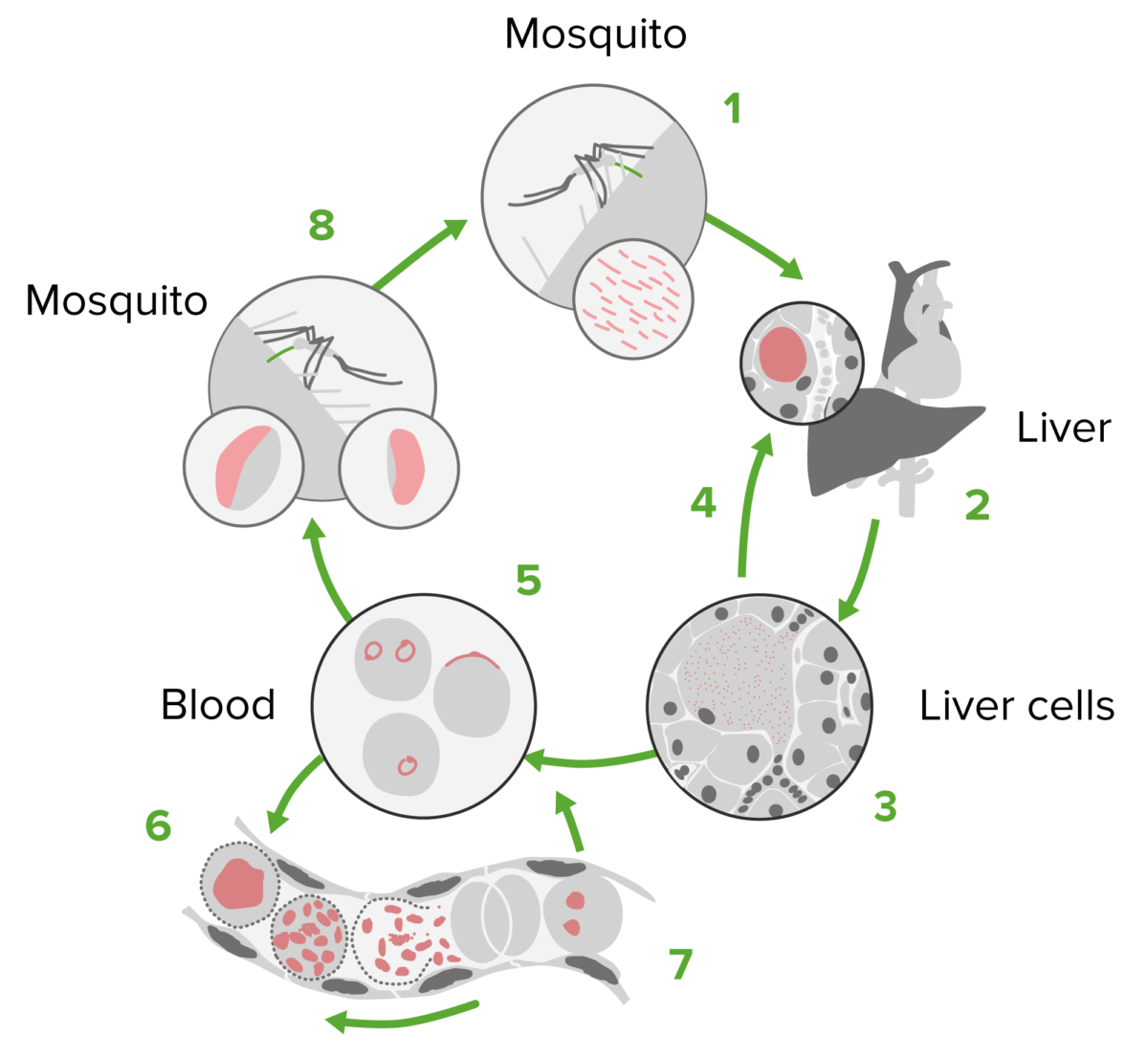

Plasmodia Life Cycle and Prophylaxis

The treatment of malaria is targeted at different stages of the Plasmodium life cycle:

- Human liver stage: targeted with tissue schizonticides

- Human blood stage: targeted with blood schizonticides

- Gametocyte stage: targeted with gametocides

- Human liver dormant stages: Hypnozoites can form in P. ovale and P. vivax infections and are targeted with primaquine or tafenoquine.

Treatment consists of 3 steps:

- Identification of the infecting Plasmodium species

- Identification of drug susceptibility of the infecting Plasmodium

- Determined by geographic origin of infection

- Patient’s clinical status

- Avoid the same drug for treatment if it was used prophylactically

Malaria prophylaxis and prevention

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) prophylactic regimens are based on a traveler’s geographic region.

- Travelers should consult local guidelines (will vary from country to country and with seasons)

- Principles of prevention

Types of Malaria Pills

Your doctor will likely choose the drug that’s recommended for the area where you’re traveling. It might be one of the following:

- Atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone): You’ll take this pill daily, starting 1 to 2 days before your trip, and you’ll keep taking it for a week afterward. Side effects of this drug are less common than for other drugs, but pregnant women or people with kidney problems shouldn’t take it. Atovaquone-proguanil also costs more than some other malaria drugs.

- Chloroquine: This drug is taken once a week, starting about 1 to 2 weeks before your trip and continuing for 4 weeks after. But chloroquine is rarely used anymore, because it no longer works against P. falciparum, the most common and dangerous type of malaria parasite. Your doctor might recommend it if you’re going to areas where there’s malaria not caused by P. falciparum.

- Doxycycline: This daily pill is usually the most affordable malaria drug. You start taking it 1 to 2 days before your trip and continue taking it for 4 weeks afterward. Side effects include upset stomach, bad reactions to the sun and, if you’re a woman, yeast infections. Pregnant women and children younger than 8 shouldn’t take this pill.

- Mefloquine: Begin taking this weekly drug 2 weeks before travel and continue until 4 weeks afterward. Pregnant women can use it, but people who have a history of seizures, severe heart problems, or psychiatric conditions shouldn’t. Side effects can include dizziness, sleep disturbance, and psychiatric reactions.

- Primaquine: This weekly drug is taken 1 to 2 days before travel, continuing until 1 week afterward. Side effects can include an upset stomach. Pregnant women shouldn’t take Primaquine. Nor should people who have a condition called G6PD deficiency, in which certain drugs cause red blood cells to break down.

- Tafenoquine (Arakoda, Kozenis, Krintafel): This new drug is recommended for adults aged 16 years or older who are traveling to malarious areas. It is to be taken daily for 3 days prior to travel to the region, once a week while there, then a dose seven days after exiting the area.

Tafenoquine can also be used to stop a relapse in those who are already infected with malaria. The drug has been known to cause an upset stomach. It should not be taken by those younger than 16, pregnant women and those with G6PD deficiency.

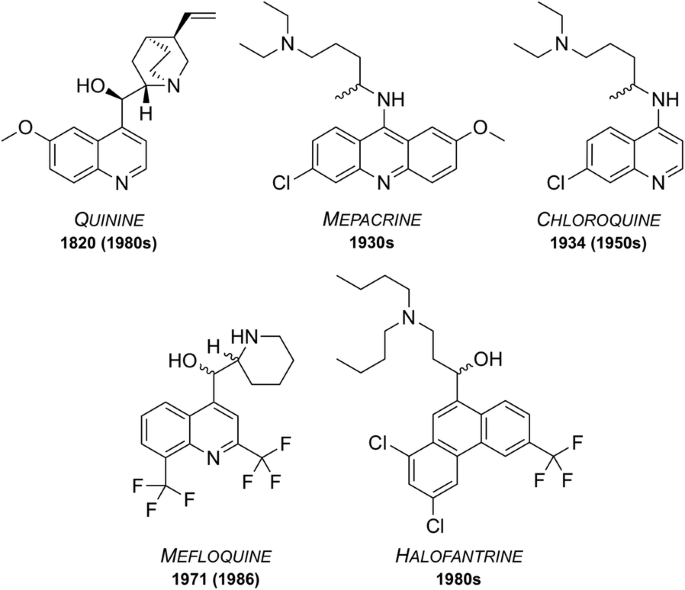

Since the isolation in 1820 of quinine, the first chemically purified effective treatment for malaria, a number of other natural and synthetic compounds have been developed. However, as time passed, strains of the parasite began to show signs of resistance towards these drugs, rendering them less effective. Accordingly, their use has ceased or is restricted to particular situations.

Quinine

First isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, quinine has been used as one of the most effective treatments for malaria to date. Resistance was first reported in the 1980s and as of 2006, quinine is no longer used as a front-line treatment for malaria but is still on the WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines (MLEM) for the treatment of severe malaria in cases where artemisinins are not available.

Mepacrine

Mepacrine (a.k.a quinacrine) was predominantly used throughout the Second World War as a prophylatic, sold under the trade name Atabrine. This compound is a derivative of methylene blue, another anti-malarial that was discovered in 1891 and found to be an effective treatment for malaria. Its use has declined over the years but methylene blue and its derivatives are, however, the subject of increasing current interest and it is currently in clinical trials as a combination with primaquine (vide infra). Mepacrine itself is no longer used today due to the high chance of undesirable side effects such as toxic psychosis.

Chloroquine

During the 1940s, chloroquine (CQ) was used to treat all forms of malaria with few side effects. Resistance to CQ was first reported in the 1950s and over the years many strains of malaria have developed resistance. Indeed, resistant strains (K1, 7GB, W2, Dd2, etc.) of the malaria parasite are now used in potency evaluation assays as a way of showing efficacy. Chloroquine is on the MLEM for the treatment of P. vivax in regions where resistance has not developed.

Mefloquine

Mefloquine was developed in the 1970s by the United States Army [22] and is still used today, also being one of the medicines on the MLEM. Originally introduced for the treatment of chloroquine-resistant malaria, it has been used as both a curative and a prophylactic drug. Resistance was first reported in 1986. It is thought that the structurally related quinoline drugs (such as quinine, mepacrine, chloroquine and mefloquine) act through the disruption of haemoglobin digestion in the blood stage of the parasite. These drugs are commonly used in combination with a complementary drug (e.g. mefloquine and artesunate, sold as Artequin™) to reduce the chance of resistance development to the quinoline family of compounds. Mefloquine is commonly sold in its racemic form under the brand name Lariam®, however it is no longer widely used due to the perception of central nervous system toxicity that has been suggested to affect a large number of its users.

Halofantrine

Developed between the 1960s and 1970s by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, halofantrine was initially used for treatment against all forms of the Plasmodium parasite. Its use has diminished over time due to a number of undesirable side effects, such as the potential for high levels of cardiotoxicity. It is only used as a curative drug and not for prophylaxis due to the high toxicity risks and its unreliable pharmacological properties. Halofantrine is still used today, under the brand name Halfan™, but only in cases where patients are known to be free of heart disease and where infection is due to severe and resistant forms of malaria

What If I Get Malaria Anyway?

If you have symptoms of malaria, get help at once. It’s important to start treatment as soon as possible before it gets more severe.

Your doctor will try to decide what type of malaria infection you have in order to figure out which drug you should take. This is important, as some malaria parasites have become resistant to certain drugs. Your doctor may prescribe a combo of malaria medications to help you avoid this drug-resistance problem.

The type of drug you’re prescribed will depend on several things, including:

- The type of malaria infection you have

- Your age

- Your physical condition

- Whether you took medicine to prevent malaria and, if so, what kind

- Whether you’re pregnant

These drugs may be swallowed or taken through an IV line for people with severe cases.

Many of the medicines used to treat malaria are the same ones listed above for preventing it. You shouldn’t take the same medicine to treat malaria that you took when you were trying to prevent it.

Add comment